A report from an American university student, living in Preah Vihear Province

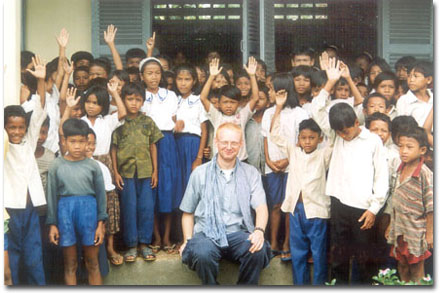

A report from an American university student, Mathew Madden, who lived and worked in the remote village of Rasmei, in Preah Vihear Province, at #3 The Elaine and Nicholas Negroponte School, as a teacher

X-Originating-IP: [203.127.100.5]

From: “Matthew L. Madden” <mohamadden@hotmail.com>

To: bernie@media.mit.edu

Subject: re: thank you

Date: Thu, 27 Jul 2000 01:14:40 MDT

Mime-Version: 1.0

Dear Mr. Krisher,

Following is my final report of my volunteer activities with Japan Relief for Cambodia, as I promised:

>From May 14 to May 28 I spent time at the Future Light Orphanage observing the teachers and students and helping to teach. I spent part of each day in the English class observing teaching, and the rest of each day in the computer lab. In English class I observed the teachers strategy for teaching the kids, and then followed the same pattern when he gave me time to teach.

When the computer teachers taught lessons to the children, I wrote them down in Khmer also to get a feel for the lessons and to provide myself with some lesson materials when I went to the provinces. When the children were given practice time to paint pictures or type I usually tried to find children who needed individual help and assist them. During this time I also learned quite a bit about how to use MAC paint program that they use, and spent some time becoming familiar with the Khmer font layout that they use.

My time spent at the orphanage was helpful in providing me with a basic familiarity with Khmer classroom systems, relationships, and behaviors; a feel for the kind of text needed to teach beginning English to Khmer children; a basic understanding of computer programs and fonts used; a Khmer vocabulary for computer-related concepts and objects; and some computer lessons that I copied during computer class.

>From June 1 until July 14 I spent five days a week teaching English and computers to students of the Khum Reaksmey (Elaine and Nicholas Negroponte) Elementary School in the Rovieng District, Preah Vihear Province. I alternated between English and computers for four hours from 7 a.m. until 11 a.m., and then for another four hours from 1 p.m. until 5 p.m.

The morning classes were composed of children who studied their normal public school curriculum in the afternoon, and vice versa. Three of the four English classes were mixed classes of second to fifth graders, and one class was strictly first graders. For the first couple of weeks all of the children learned to write and recognize the characters of the English alphabet. Emphasis was placed on writing correctly and neatly, using the lines in their books to follow examples given by me. Homework was assigned and corrected each day.

I soon realized that the first grade class needed to take it slower than the other classes, so they soon moved into their own pace apart from the others. The first graders also spent time in each class period learning to sing a song: Head, Shoulders, Knees, and Toes. I had discovered that their attention span was especially short, and the singing helped to attract their interest in learning each day. However, by the time the children had finished learning the alphabet, I found that some of the first graders who hadn’t quit by then knew the alphabet better than many of the older children.

Once the children had covered the whole alphabet from A to Z, things became more difficult. I didn’t know how to proceed from there. At first I tried just to teach them the basics of reading by putting letters and sounds together and was surprised by their lack of understanding. I tried to start simple and give them two-letter words with only short vowel sounds, but even then there were only certain of the brighter students that got the concept. I found that they expected their teacher to tell them what to say and they would just repeat after me, rather than figuring the words out on their own using the letters. Perhaps this is a reflection of traditional Khmer classroom systems. In fact, this reluctance to figure things out and solve problems on one’s own based on what had previously been learned, without waiting for step-by-step guidance from the teacher, was witnessed in computer classes as well. Because of the constant frustration felt by both myself and the children when trying to learn reading, I felt that maybe I should try a different approach and tried to teach them how to speak some basic sentences and greetings. Feeling that they were just writing what I wrote and saying what I said, but not understanding why words are said the way they are said, I was continually pulled back into teaching reading as well. I sort of improvised from day to day based on my students’ responses and alternated between the two approaches, trying to find a balance that worked. I felt that English is a huge and convoluted subject to attack, and felt insecure on just how to go about it with people who had never learned it before. I often felt that maybe I was trying to go too fast and make it too advanced, and then tried to slow it down. I realized that it has to be very simple and slow-paced and began to wish that I had a good beginner’s English textbook for children that good give me some guidance on how to do it.

Finally I procured the textbook Let’s Go in Phnom Penh. That is the first textbook used to teach the orphans in the FLO, and seems to be very effective. It is very simple and is geared towards young children. I was able to use the first two lessons in my final week of teaching. (I feel very strongly that Let’s Go would be an effective teaching tool to use with the children, especially if used in conjunction with the Let’s Go cassette tapes. I left a copy of Let’s Go Book 1 and Book 2 at the school when I left, as well as the tapes, although there is nothing to play them on.)

When I left my students they were fairly familiar with the alphabet, had a very vague understanding of how to read single-syllable two or three letters words (some students better than others), and could say some basic sentences like greetings, asking and telling names, and asking and answering ‘What is this?’ On their last couple of days they learned how to use an English-Khmer dictionary to look up words, and several students caught on much more rapidly than I expected.

The computer classes each consisted of five children, chosen by their teachers because of their skills and motivation. It was decided that five would be the maximum, since there was only one computer. Even with only five students, this still meant that the approximately 30 days of instruction was the equivalent of maybe six days at the FLO, in terms of the time that each child got to spend with the computer.

The early lessons consisted of learning the names and functions of basic parts of the computer. Then the children learned how to use the mouse, using some lessons I had copied at the FLO and one that was innovated on my own. I found that the children were extremely uncomfortable and awkward with using the mouse and were even a little afraid of using the computer. Giving the children time to paint pictures was an excellent way to help them get comfortable with the computer and with manipulating the mouse. Whenever there was a lesson, it occupied the first part of class, and then the rest of the time was spent in using either the painting program or typing Khmer script in Microsoft Word. Many class periods, probably most, had no lesson and were spent entirely in using the computer to practice typing or drawing.

Before my last week at the school I was able to procure photocopies of a Khmer lesson booklet on Mac-OS at the FLO in Phnom Penh. This was used to teach the children during my last week, and is a priceless resource to leave with them in their classroom. I also procured some lesson books on Microsoft Word to leave with them, though I never taught from them and believe that they are perhaps too advanced for my students at this point.

When I left my computer students, they were getting more familiar and comfortable with using the computer and manipulating the mouse and keyboard. They were getting faster and more confident in typing, and more creative and resourceful in their drawing. They have basic knowledge of how to turn the computer on and off, start relevant programs, turn Khmer fonts on and off, and save and open files (though they still show a reluctance to do these things on their own without step by step instructions and guidance from the teacher.)

My own opinions and suggestions on how the children could continue to learn

to use the computer if they don’t have a new teacher soon is that perhaps one of the older, more trustworthy children could be given a key to the classroom and could open the class during certain times so that the computer students can have an opportunity to use the computer. I tried to give them enough self sufficiency to be able to start and use the programs they need without help, though they may need to depend on their copied lessons if they can’t remember. I imagine it would also be necessary to have access to someone who knows Macintosh well from time to time to help solve problems and maintain the computer in proper working order. There are also dictionaries, English books, and computer lessons there in the classroom for the children to use.

While in Reaksmey I lived in the house of a local Cambodian family. The food provided by them was good and I had virtually no problems with it (though I did give them a good explanation of what I can’t eat from the beginning.) I slept on a grass mat like they do and bathed from a water pot in the front yard wearing a cloth around my waist, just like they do. I used the toilet facilities at the school, since locals don’t have toilets. I felt that my physical accommodations were adequate, thanks to the presence of the school, and have no complaints. I actually enjoyed being able to live with rural Cambodians and live like they do, and it is something I’ve wanted to do for a while.

The emotional and psychological aspects were not always easy, I must admit.

It was difficult to become fully accepted as a normal person by the community. I often felt frustrated by their seeming rudeness or condescension and often felt that they treated me more as a novelty or object of ridicule than a human being. My students were frightened of me at first and wouldn’t talk to me or answer my questions; many children would run away if they saw me coming.

By the end of my time people had gotten somewhat more used to me and my students were starting to open up and show love to me. I became quite close to the family I lived with and with many of my students, and it was hard to leave them. Many community members lost their fear and/or contempt of me and began to treat me more like person than an exotic animal. I was invited and received with honor at community events like wedding receptions. Over all I had a positive experience, despite the occasional negative feelings mentioned above.

I recognize that the emotional and psychological frustrations that I experienced are natural symptoms whenever two very different cultures come in contact ñ it is often called ‘culture shock.’ I also recognize that the people there have never experienced the presence of an outsider like they did with me, and they didn’t yet know how to handle it like maybe we or even the people in Phnom Penh would. I am very grateful for my fluency in the Khmer language and my familiarity with Khmer society and customs, without which I doubt I could have survived. I simply can’t imagine someone doing what I did for very long at all without knowing at least the language, and I see that as a large potential limiting factor of using volunteers. I imagine that a person could manage to procure at least the physical necessities for living without knowing Khmer, but I personally feel that the psychological and emotional isolation could become too much to cope with. And that doesn’t even take into account problems of trying to instruct Khmer students who can’t speak English.

I would like to finish by thanking you tremendously for the opportunity you gave me. I felt that my time in Reaksmey was a very good experience, and I have good memories of it. Like I said, it provided me with an opportunity to do something I’ve wanted to do for a long time and thought that I never would. I hope I was also able to touch the lives of some Cambodians. I would also like to thank you for giving Jeremy and I a place to stay in Phnom Penh for our last couple of weeks here before we return home. I can’t tell you how helpful that is to us, and it is tremendously appreciated.

Good luck in all of your current and future endeavors to help the people of

Cambodia.

Best regards,

Matt Madden